‘Alive and well’: Wandering Spirit narrative reexamined at commemoration event

At Fort Battleford, there is a headstone with the names of eight men who were part of Canada’s largest mass hanging following the resistance of 1885. Among the names etched in the stone is Wandering Spirit.

The mass grave, however, harbours a secret: beneath the earth, his body is not among those who lie beneath, but rather resides in a cemetery on a reservation in Montana.

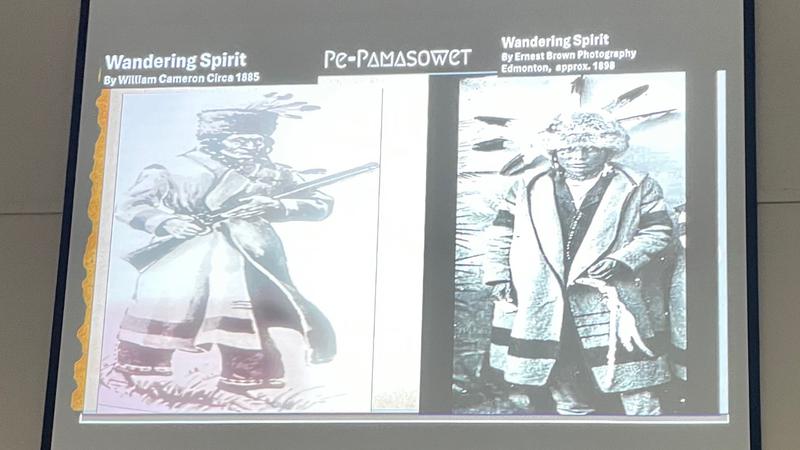

Pe-Pamasowe’t, the warrior known as Wandering Spirit, long understood by conventional history to have been one of the eight executed at the Fort, in fact lived.

In a special day-long event, hosted in collaboration with Poundmaker Working Group and Parks Canada, titled Pe-Pamasowe’t (Wandering Spirit): The Truth, His fate and Legacy, 1885 Rebellion, 140-year commemoration was held at both the Fort and the Western Development Museum on Thursday.

The day began with a pipe ceremony, tour and knowledge sharing at the fort before activities moved over to the museum which included an open mic period that featured guest speakers Saddle Lake Leadership-Chief Jason Whiskeyjack and Councilman Eric Shirt.

Eric Tootoosis, grassroots conglomerate of Poundmaker Working Group served as the emcee and spoke to the town and its fort becoming the centre of their history as that was where the trading post and also where the provisions were kept.

“We have a very unique survival story,” he said.

“Prior to treaty making, prior to Confederation 1867, the Crown invited the Indians to England.”

He explained that at the time in the early 18th Century, a delegation of Mohawk and Mohican Chiefs answered Queen Anne’s request. During the visit, they were told of the Crown’s plan for the land and the “New way of life.”

Eric Tootoosis addresses the audience. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)

Eric Tootoosis addresses the audience. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)The delegation members were treated as diplomats and met with scholars, writers and council to co-develop the first “Indian Act” that complimented the Indigenous understanding of the land and resources.

“It stipulated everything to be shared equally,” he said.

Later, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was signed by King George III, which recognized Indigenous land rights and affirmed Treaty-Crown relations.

“Both instruments were co-developed by Indians.”

Fast forward 100 years and a new act was in place, this time with a new goal: “Eliminate the Indians, erase the races,” said Tootoosis.

“We have survived ladies and gentlemen and there are survivors here.”

A different narrative

The overarching goal was to teach a different narrative from the one found in history books.

“We have a lot of evidence of people who were alive, the people who were there, who the leadership was and how it was structured,” said Leah Redcrow, executive director of Acimowin Opaspiw Society.

She explained that doing research has been an important step in correcting the longstanding colonial narrative.

“It’s somebody’s way of interpreting our history for us that they didn’t get consent to do – thinking he had no family, thinking he’s some imaginary person, he’s not,” said Redcrow, adding people must always think about the families and communities.

“How is that going to make them feel – their children, their grandchildren like my relatives in (Rocky Boy Reservation) and in Saddle Lake, they’re not happy that our ancestor’s name is on a headstone, and we know that he’s not in that grave,” she said.

“It’s hurtful for them.”

Speaking of the proper protocol, Redcrow said when conducting research or writing about anyone, it is imperative that there is permission from the community.

“Before you write anything about anybody who’s not yourself, get consent. Get consent from the families, confirm what you see in the documents, go talk to the families and make sure that’s the truth.”

Redcrow, who comes from the Snake Hills Band in Saddle Lake said understanding how a Plains Cree society operated was crucial to understanding the history of Wandering Spirit and his brothers. She explained that it was a hereditary governance and is organized much the same way as the European monarchy.

“The (federal) government is complicit in misappropriating our history. The Plains Cree leadership had pure bloodlines,” she said.

As such, A Saulteaux member for example, could not be placed as the head of a Plains Cree warrior society.

“What their number one goal was after the rebellion was to abolish the tribal system,” she said.

“Well, what’s the tribal system? The tribal system is our original hereditary form of governance and the leaders that we had – they were born into those positions, and they stayed in those positions until the day that they died.”

1885

Setting the backdrop to the events that would eventually lead to the warrior escaping from the police and making his way to Montana was the resistance.

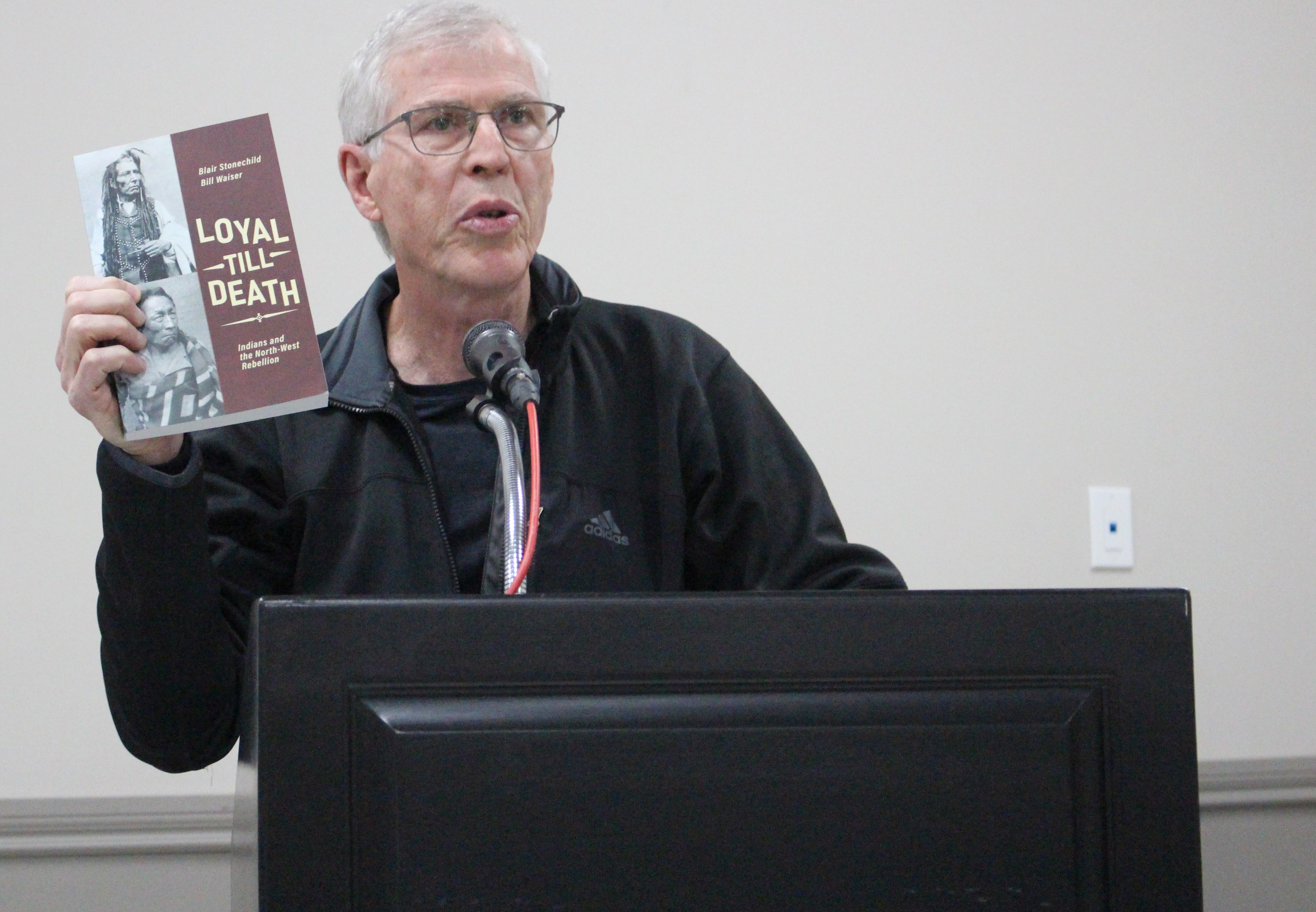

“In March 1885, Louis Riel declares his provisional government, he demands the surrender of Forts Carlton and Battleford,” said Historian Bill Waiser, who has studied the resistance for four decades and has written extensively on the subject.

“Riel’s strategy at the beginning was to take hostages, make threats and force the Canadian government to negotiate.”

Waiser, providing the societal context that created the environment for the events to follow, said that it was after a clash between the Northwest Mounted Police and the Metis forces near Duck Lake a week later, a negotiated settlement was no longer an option.

“The John A. Macdonald government upon learning of this battle quickly mobilizes a military force to be sent to Western Canada,” he said, adding that Prime Minister’s nickname was ‘Old Tomorrow,’ referring to Macdonald’s penchant for procrastination.

“Why does he act so quickly? Well, he acts so quickly in March 1885 because he believes that the First Nations have joined with the Metis.”

Macdonald came to that conclusion because the Battle of Duck Lake took place on what is now known as Beardy’s and Okemasis Cree Nation and thus he believed he was dealing with combined forces.

“Newspapers of the day pick up that interpretation – that’s a grand alliance between Metis and First Nations people,” he said.

More than that, Sir Charles Tupper, then high commissioner in the United Kingdom sent a telegram to Canada saying that the British believe there is an “Indian uprising” happening in Western Canada.

“That’s how Duck Lake’s interpreted.”

In reality, Waiser said the First Nations wanted nothing to do with Riel’s plans.

“First Nations leaders made a solemn vow during the treaty negotiations to live in peace with Queen Victoria,” he said.

“They made that vow in the presence of the Creator, and they’re not prepared to break that pledge – even if Canada was not honouring the spirit in terms of the treaty.”

Historian Bill Waiser holds up a book he cowrote and speaks to the significance of 1885. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)

Historian Bill Waiser holds up a book he cowrote and speaks to the significance of 1885. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)According to the colonial historical record, in April 1885, Wandering Sprit and warriors were starving. Led by Big Bear, they went to Frog Lake to murder Indian Agent Thomas Quinn.

Through research presented during the event, Redcrow asserts this was not the case – not only did Wandering Spirit not kill Quinn as Saddle Lake had their own Indian Agent – John Mitchell, but he also had no affiliation with Big Bear. Rather they used his name to throw the authorities off.

One of Wandering Spirit’s brothers – Peter Brighteyes – was fluent in Cree, English and French. During the uprising, he would send letters and other communications but sign them as Big Bear.

“That we have also confirmed – he was not the leader of our people,” she said.

The band was also quite wealthy. Through trading agreements with the Hudson’s Bay Company and others, at close of the fourth quarter of the 1884 fiscal year, the Snake Hills Saddle Lake Band made the equivalent of $1.4 million.

“They obviously were not starving, and they were not desperate.”

The children

In her presentation, Redcrow explained the vengeance they sought, which is what led them to Frog Lake, was on the Catholic priests who had taken the Snake Hills children to their school and were teaching them a doctrine that went against their cultural teachings.

“This had nothing to do with the Indian agent, it had nothing to do with food. There was a major, major, major spiritual clash that happened but also a major clash of natural law that happened.”

Redcrow explained at the time, the only way a community could have a school was if it also had a church, the latter of which the band did not allow. By removing the sons of the warrior society and relocating them to attend their school, baptizing the children and having them live with clergy, the priests violated natural law.

“When they got to Frog Lake, they surrounded the church,” she said, adding the priests knew what was about to happen.

“The priest told them, ‘Don’t commit any excesses’ while the service was going on so, they knew that they were coming for them.”

What’s more, Quinn knew about what was coming and according to the research, he sent the police away the day before to Fort Pitt.

As a result, Fathers Fafard, Marchand, Micheaux and an unknown lay brother were taken to a knoll out of sight and put to death in what is now called the Frog Lake Incident.

“The priests were shot execution style and then they were scalped, and their hearts were cut out,” she said.

“This right there, it tells us this was a vengeance killing,” said Redcrow, adding it wasn’t random – it was planned.

“What it means when you get scalped by one of these warriors, it means that…basically you’re one of their most hated enemies.”

Afterwards, as the church was burned, they had a chicken dance.

The other men, including the agent and farming instructor were killed by Little Bear – Big Bear’s son and others.

“The Indian agent was still laying where he was killed and so were all those other people,” she said.

“That tells us that those were unplanned and weren’t part of anything that they went there for.”

Upon reading the documentation, made up of scores of communications, death certificates and pay sheets, it solidified for the researchers what was truly at issue.

“It was about the children and this was about what happened with those priests,” said Redcrow.

A turncoat identifies the men

At the time, Frog Lake and Saddle Lake were, due to geography, essentially viewed as one reserve as they shared Dog Rump Creek. The understanding of what took place that day in early April was incomplete as the Plains Cree’s knowledge wasn’t considered.

Meanwhile, it was a “turncoat” that led to Wandering Spirit’s arrest as he was crossing Saddle Creek on horseback.

“When they arrested Wandering Spirit, he broke free of his ball and chain and he escaped,” she said, adding he went to his parents first for provisions before making his way to Montana.

It was in the fall of 1885 that Macdonald requested those involved in Frog Lake be brought up on murder charges. The official record of history says the men were hung on Nov. 27 that year. The executive director, however, explained the government was implicated in hanging the wrong men.

One of the buildings at Fort Battleford. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)

One of the buildings at Fort Battleford. (Julia Lovett-Squires/battlefordsNOW Staff)“All the people that are on that headstone were alive and well in Rocky Boy, Montana decades after that happened,” she said.

The young country, it seems, knew it.

“Canada was trying to deport them back.”

Once crossing the border and arriving at Rocky Boy, he was met by roughly 500 family heads from the band that made a mass exodus as asylum seekers.

Big Wind

“Basically, the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation, those people are the historic satellite Snake Hills band members,” Redcrow said.

For his part, Wandering Spirit changed his name to Big Wind – his brother’s name – when arrived.

According to records, he remarried and had children though he wished to return to his home. Later, he made enquiries to the Indian Commissioner as to whether he would be killed if he came back.

Upon his death at the age of 83 in 1925, Pe-Pamasowe’t’s death certificate, issued by the State of Montana, listed his cause of death as “old age.”

—

julia.lovettsquires@pattisonmedia.com

On BlueSky: juleslovett.bsky.social